톨로사-헌트증후군을 모방한 침습 아스페르길루스증

Invasive Aspergillosis Mimicking Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome: A Case Report

Article information

Trans Abstract

Invasive fungal infection remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients. Invasive fungal sinusitis can present as a Tolosa-Hunt syndrome (THS) or orbital apex, leading to frequent misdiagnosis. Accurate diagnosis of fungal infection invading the cavernous sinus or orbital apex is essential to reduce mortality through early antifungal treatment and reduce the risk of worsening with steroid treatment due to misdiagnosis of THS. Herein, we report a case of invasive fungal sinusitis mimicking THS.

Fungal sinusitis is a fungal infection in the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, divided into invasive and non-invasive types [1]. Fungal sinusitis is classified into allergic, chronic non-invasive (fungus ball), chronic invasive, granulomatous invasive, and acute fulminant invasive fungal sinusitis based on histological features [1,2]. Fungal sinusitis encompasses a wide variety of infections, from relatively innocuous to rapidly fatal [1]. While non-invasive forms such as fungal ball or allergic sinusitis usually stay limited to the sinuses with good prognosis, invasive fungal sinusitis, which usually affects immunocompromised individuals, is rare but potentially lethal condition [2]. Especially, invasive fungal sphenoid sinusitis is more aggressive than other sinusitis because it can cause painful ophthalmoplegia or vision loss through invasion of surrounding structures such as the cavernous sinus, orbital apex, optic nerve or other cranial nerves, internal carotid artery, and pituitary gland [1,2]. Tolosa-Hunt syndrome (THS) is a painful ophthalmoplegia caused by chronic idiopathic granulomatous inflammation of the cavernous sinus and superior orbital fissure [3]. Thus, invasive fungal infections of sphenoid sinus can mimic clinical features of THS, leading to misdiagnoses [2,4].

We describe a case of 80-year-old immunocompromised woman presented with THS was finally diagnosed as invasive aspergillosis invading orbital apex and cavernous sinus.

Case

An 80-year-old female who is immunocompromised with diabetes mellitus, complained of headache for 2 weeks and ptosis, ophthalmoplegia, and decreased visual acuity in the left eye for 1 week. The patient did not complain of symptoms such as rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, hyposmia or fever. On neurological examination, she had ptosis and impaired eye movement on the left eye. The visual acuity of the right eye was 0.8 decimal, while the left eye could only count fingers at a distance of 30 cm. Ophthalmologic examinations reported ‘incomplete palsy of the left abducens and oculomotor nerve’.

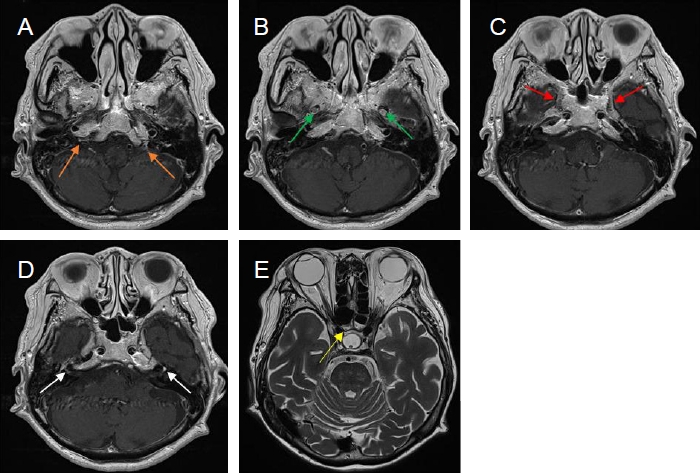

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed inflammation in the left cavernous sinus and orbital apex. This suggests the possibility of THS based on clinical and imaging evaluation. However, there was mucosal thickening and fungus ball in left sphenoid sinusitis and adjacent bone erosion on orbit MRI and ostiomeatal unit computed tomography (OMU-CT) (Fig. 1). The diagnosis of fungal infection was made based on invasive lesions discovered on CT and MRI and risk factors for infection such as old age and diabetes.

Initial brain MRI images. (A) Fat-suppressed axial T2-weighted image shows diffuse fat infiltrating lesion expanding along left orbital apex, superior orbital fissure and cavernous sinus (arrows). (B, C) Fat-suppressed contrast-enhanced axial and coronal T1-weighted images reveal enhancement in left optic perineural region, orbit apex and cavernous sinus (arrows). Mucosal thickening and enhancement with central dark signal intensity in left sphenoidal sinus (arrowhead) are noted. (D) Axial bone-window CT shows bone erosion in left sphenoid sinus (arrows). MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CT, computed tomography.

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (47.0 mm/hr, Reference range: 0-20 mm/hr) was elevated but other Immunologic serum markers including antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, rheumatoid factor, anti-Ro/La antibodies, C3, C4, and serum protein electrophoresis were normal. The Aspergillus antigen of the serum was positive. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis showed elevated protein levels (144.3 mg/dL) without pleocytosis.

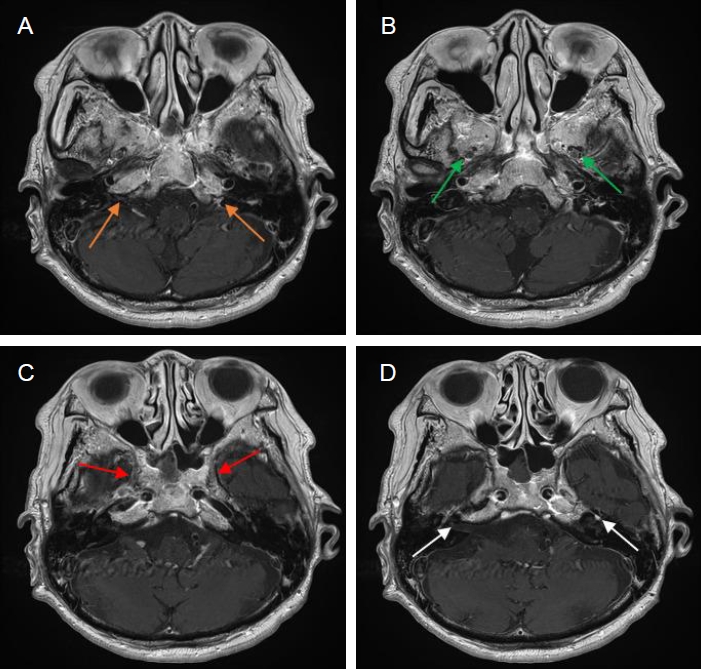

Endoscopic sinus surgery including sphenoethmoidectomy, biopsy, and irrigation revealed sphenoid mycetoma and inflammation of sphenoid mucosa. Pathological examination of the collected tissue confirmed Aspergilloma. For the Invasive aspergillosis, intravenous (IV) voriconazole was started, but the patient developed hallucinations and acute kidney injury associated with voriconazole, prompting a switch to amphotericin B. Approximately three weeks later, the patient experienced new symptoms of left facial numbness, right facial weakness, bilateral decreased visual acuity (decimal 0.1 in right eye, light perception only in left eye), dysarthria, and dysphagia. A Follow-up brain MRI revealed new findings of right sphenoid sinusitis and inflammation of in both jugular fossae, maxillary and mandible branches of both trigeminal and both facial nerves (Fig. 2). Considering the invasive aspergillosis had progressed, IV caspofungin and IV voriconazole were added, and these three anti-fungal agents were used for one week. For the symptoms related with multiple cranial neuritis, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy was attempted twice at 2-week interval. Partial improvement of visual loss (decimal 0.32 in right eye, hand motion in left eye), ophthalmoplegia, facial weakness and numbness, and bulbar palsy was observed after IVIG. The anti-fungal treatment was changed to IV isavuconazole alone for 2 weeks, and then oral voriconazole was administered for 4 months. The anti-fungal agents were administered for a total of 7 months. Symptoms gradually improved, and at 8 months after onset, visual acuity was much improved (decimal point 0.4 in the right eye, hand movements in the left eye) and other symptoms such as ptosis, ophthalmoplegia, facial weakness and bulbar palsy completely resolved with decreased enhancement on follow-up brain MRI (Fig. 3).

A follow-up brain MRI images. (A-D) Contrast-enhanced axial T1-weighted images show abnormal enhancement in both jugular fossae (orange arrows), maxillary (green arrows) and mandible (red arrows) branches of both trigeminal nerves and both facial nerves (white arrows). Note complete regression of left sphenoidal sinusitis. (E) Axial T2-weighted image demonstrated right sphenoid sinusitis (yellow arrows). MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

A last brain MRI images. (A-D) Contrast-enhanced axial T1-weighted images reveal interval improvement of abnormal enhancement in both jugular fossae (orange arrows), maxillary (green arrows) and mandibular (red arrows) branches of both trigeminal nerves and both facial nerves (white arrows). MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Discussion

The syndrome of painful ophthalmoplegia, THS, is characterized by periorbital or hemicranial pain, accompanied by third, fourth, or sixth cranial nerve palsies, and sensory change in the distribution of the ophthalmic division of the fifth cranial nerve [3]. Occasionally, there have been reports of optic nerve dysfunction in THS, suggesting involvement of the orbital apex in the pathological process [3].

THS is diagnosed when painful ophthalmoplegia is caused by chronic idiopathic granulomatous inflammation affecting the cavernous sinus and superior orbital fissure [3]. In addition to inflammatory cause, painful ophthalmoplegia can be caused by a variety of causes such as tumors, vascular malformations, thrombosis, and infections, so it is necessary to thoroughly rule out the possibility of other causes [3]. Occasionally, there have been reports of optic nerve dysfunction in THS, suggesting involvement of the orbital apex in the pathological process. 3 Steroid therapy has markedly beneficial effect for THS. However, clinical signs of THS may be due to infection, in which case steroid treatment may actually worsen the disease, so careful evaluation is essential to determine the etiology [3]. As steroid-responsive THS is diagnosed based on clinical manifestations, there are diagnostic dilemmas and risks in the differential diagnosis process.

Invasive fungal sinusitis, a rare but life-threatening infection, predominantly affects immunocompromised individuals [1]. The immunocompromising causes of patients with invasive fungal sinusitis include hematologic malignancies, chemotherapy-induced neutropenia, AIDS, or diabetes mellitus [1]. Aspergillus, Fusarium, and Zygomycetes organisms and pigmented molds are most often implicated in cases of invasive disease [1,5]. The definition of invasive fungal sinusitis lies in the presence of fungal hyphae within the mucosa, submucosa, bone, or blood vessels of the paranasal sinuses [6]. Despite completing treatment, up to 80% of patients experience death or further morbidities (ranging from 20 to 80%) [7]. In the previous report, the overall case fatality rate was 58% and was highest in patients with central nervous system or disseminated aspergillosis (88.1%) [8]. Aspergillosis, especially in the sphenoid sinus, may exhibit diverse clinical manifestations of THS, depending on involvement of cavernous sinus and orbital apex structures [4].

When suspecting invasive fungal sinusitis, a comprehensive approach involves a panel of blood tests, imaging, and tissue biopsy. 1 Serum galactomannan Aspergillus antigen is being investigated as a screening test for aspergillosis, demonstrating high specificity (100%) and positive predictive value (100%) with low sensitivity (44.8%) [9].

Although not sufficiently sensitive or specific to confirm diagnosis, imaging techniques such as CT and MRI may demonstrate suggestions of fungal sinusitis [5]. Unilateral involvement of the ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses is commonly observed [6]. CT demonstrates sinus opacification with or without associated flocculent calcifications, a hyper-attenuating fungus ball located in central area of the sinus, and infiltration of adjacent soft tissue or bone destruction [6]. In MRI, fungal balls can be suggested by the presence of an isointense signal within the fungal mass on T1, in conjunction with dark-signal lesions surrounded by high-signal enhancement of the mucosal walls on T2 [6]. Histopathologic studies in acute invasive fungal sinusitis reveal hyphal invasion of the mucosa, submucosa, nerves, and blood vessels, including the carotid arteries and cavernous sinuses [1].

The standard approach for treating fungal sinusitis typically involves a combination of surgical debridement and antifungal therapy [7]. Endoscopic sinus surgery primarily aims to establish early diagnosis, obtain tissue samples, and perform necrotic tissue debridement [1]. The guidelines recommend either systemic voriconazole or a lipid formulation of amphotericin B as anti-fungal therapy for invasive Aspergillus fungal sinusitis [9].

In this case, an 80-year-old female was diagnosed with invasive aspergillosis, presenting with clinical manifestations of THS. MRI revealed inflammation in cavernous sinus and orbital apex accompanying with sphenoid sinusitis suggesting fungal sinusitis. Pathological examination revealed invasive aspergillosis. Despite combination anti-fungal therapy and surgical management, there were worsening symptoms and radiological deterioration. Based on the results of previous studies showing that adding IVIG to anti-fungal drugs helped improve the prognosis of fungal infections [10], we added IVIG, which improved symptoms of this patient.

Invasive aspergillosis is a potentially fatal condition if not treated early or aggressively. Diagnosis could be delayed because the initial clinical manifestations highly mimic THS. Our case highlights the importance of a high level of suspicion for possible fungal invasion in cases of THS manifestation with ipsilateral sphenoid or ethmoid sinusitis.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.